In Nigeria, literacy finds its place, even as oral Bible translation succeeds

Loh Community, Gombe State, Nigeria—

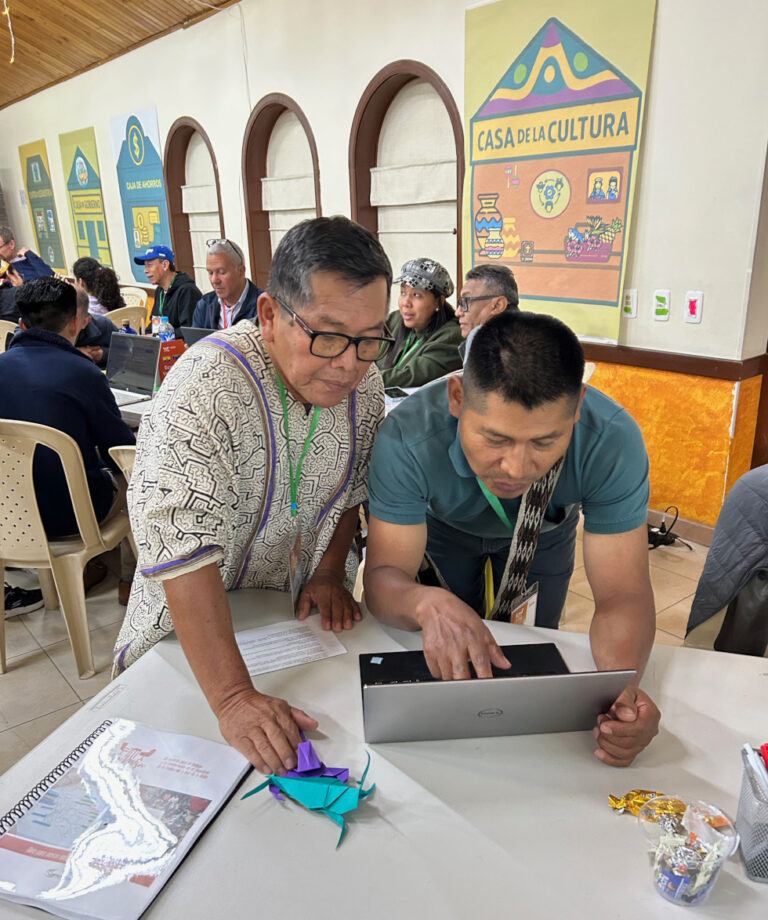

In the dusty courtyard of a village church Pastor Ibrahim Musa watches as a small group gathers under a mango tree, repeating syllables from a literacy primer as well as learning the proposed alphabet of the Loh language.

‘They come every week’, he says quietly. ‘Even when there’s no food at home, they come. That is what I call hunger for God’s Word.’

The group has already listened to recently translated audio Scriptures—a common strategy in Bible translation movements, to get Scripture to people in oral cultures without imposing the obstacle of literacy. But now, gatherings like this one are gaining momentum because the people want more.

‘It wasn’t easy at the start’, Musa says. ‘Some said, “Why should I learn to read my village language?” But now they say, “If God is speaking it, then I want to understand it better.”’

Oral Bible translation (OBT) is making remarkable strides across Nigeria, providing Scripture to communities that have never before encountered God’s Word in the language they know best. These efforts, by the Nigeria Bible Translation Trust (NBTT) and others, are leading people to deeper spiritual connection and cultural affirmation. In places where written translation might take years, OBT has fast-tracked access to the Scriptures via audio recordings, allowing communities to hear Bible stories in a way they can immediately understand and share.

Yet, as these oral initiatives expand, the quieter question of literacy is surfacing.

‘The belief is that if people can hear the Word, they can engage with it’, said Pastor Monday Ekpenyong, translation advisor for the Ekid project in Akwa Ibom State. ‘However, in practice, this assumption doesn’t always hold entirely true. We discovered that orality alone is good but not enough. We need to engage our people in our language so that they can love and cherish their language more.’

Seeking ‘a stronger foundation’

“When the translation project came to our community, it was a ground-shaking opportunity for us to have God’s Word in our own language,” said Pastor Precious Egba, an Oral Bible Translator with the Okpameri OBT project in Edo State. ‘Our people were overjoyed and warmly embraced the idea. For a long time, we only heard the Bible in other languages, English, Igbo, and Yoruba. But none of these spoke to our hearts the way our own mother tongue does.’

When OBT brought the message of hope, salvation and transformation into local languages for the first time, it sparked a sense of dignity and belonging, Pastor Egba said. ‘Yet’, he added, ‘the journey has also revealed deeper truths.’

As he and his team progressed, they began to see that oral Scriptures alone weren’t always enough.

“We noticed that some community members couldn’t fully retain or reproduce what they heard,’ he said. ‘And importantly, the sense of ownership is dropping down. … They needed a stronger foundation, basic literacy in our language, to help them engage more deeply and develop more sense of ownership, since literacy classes and development will involve more people—even the non-Christians in our communities.’

In response, some OBT teams have been integrating literacy alongside oral Scripture translation.

‘By helping people to read and write in their own language, communities not only listen but begin to own the Word, meditating on it, memorizing it and sharing it with conviction’, said Rev. Theophilus Dodo of the Initiative for the Translation and Development of African Languages (ITDAL). This, he added, is creating a stronger feeling of ownership among communities.

Grace Ishaku, a women’s fellowship leader in Gombe, recalls how literacy classes helped her not only to understand the Scriptures in her Hausa language, but also teach others.

‘When we were young, we had literacy classes in Hausa’, she said. ‘I listened but forgot quickly. But now that I have acquired the literacy of Hausa, I read, write and remember. I even teach my children. If our language also has literacy classes that are ongoing, it will help us more to understand Scripture even when it is oral Scripture.’

•••

‘In the beginning, we thought there was no need to teach people our language since it was oral translation. As time went on, we realized there is a need to introduce at least basic literacy for our people (along with) the OBT. I personally see the need for literacy because it will involve most of our people and our villages will be actively participating. This will create awareness and ownership for people to value their language as well as the oral Scripture.”

—Mrs. Mercy, Ataba project, River State

•••

‘It is now that our people start having value in the language enough to listen to Scripture in it. Literacy is a tool that will help our people to be engaged in the language through learning, speaking, listening and writing so as to avoid speaking of English and Hausa language in our churches and community gatherings.’

—Michael M. Gwadi, OBT facilitator with Loh Project, Gombe and Taraba states

•••

‘Many members of these communities perceive their languages as inferior. Without literacy to reinforce the value of our mother tongue, people often show low motivation to engage with Scripture, whether oral or written. To address this, several OBT teams have begun integrating basic mother-tongue literacy classes into their translation efforts. This includes training community members to read and write their language, along with conducting linguistic analysis to standardize orthographies.’

—Ishaya Magaji from Mbang Project Kaduna State

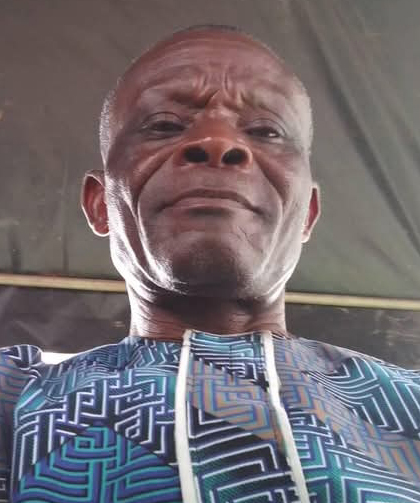

Local leaders drive the vision

In many Nigerian communities, the church is not just a place of worship, it’s a center of influence, identity and education. It feels natural, then, for churches to serve as literacy classrooms as well. As oral Bible translation and mother-tongue literacy efforts gain traction, local pastors, elders and church leaders are playing pivotal roles.

‘We see transformation’, said Pastor Joshua B. from the Banginge community, a language spoken in Balanga, Billiri and Kaltungo local government areas of Gombe State. ‘When people hear the Word of God in their own language and can begin to read it, it becomes personal. It stays with them.’

Rev. James from Ogba Project says championing both OBT and literacy helps build community, and restore a sense of identity and purpose.

“Churches have become hubs for both Scripture listening groups and basic literacy classes, with leaders testifying to renewed interest in Bible study and deeper discipleship’, he said. ‘Beyond spiritual growth, community leaders note a surge in self-worth and cultural pride among believers, especially as they see their language being honored and preserved through these projects.’

•••

“At the heart of sustainable Bible translation is a simple but powerful truth: Communities flourish when they lead their own transformation. Locals are not just participants, they are the vision-bearers. When they lead, the community listens, engages and takes ownership of the Word.’’

—Oche M. Sani, OBT trainer with Let the Lord Be Glorified

Literacy and literature as components

OBT projects across Nigeria are increasingly driven by local facilitators, literacy specialists and consultants who know the language, culture and ‘heartbeat’ of their people, Sani added.

‘To my fellow OBT practitioners: Let’s champion literacy not as an add-on but as integral to sustainability’, he said. ‘Train facilitators to model Scripture reading, collaborate with literacy advisors to design community-driven programs, and advocate for locally authored books—not just Scripture—to normalize mother-tongue literacy.’

•••

‘When a child reads Genesis 1 in their language for the first time, they don’t just hear “God created”—they see it. That visual encounter imprints truth in ways oral transmission alone cannot. Let’s keep building bridges between ear, heart, and eye.”

—Oche M. Sani, OBT trainer

‘Something shifts in their mindset’

By equipping indigenous leaders to facilitate both OBT and literacy training, NBTT trainers hope Scripture is not only heard, but deeply understood and passed on faithfully within the community. The goals are to build trust, foster pride in local identity and reinforce the message that God speaks every language—including theirs.

‘Literacy is changing the game’, said Elizabeth Mislum, a literacy coordinator working with NBTT. ‘When people begin to read and write in their language, something shifts in their mindset. They realize their language is worth something.’

Local churches are also stepping in to support this dual approach. In Adamawa State, Rev. Andrew Musa, a pastor in one of the participating villages, has seen a difference.

‘When we started with oral translation, people were excited’, he said. ‘But when we introduced literacy, they became committed. Youths who never cared about the language now use it in church. Women in our fellowship see the need for the Bible in their hearts.’

Need for materials, teachers and funds

While audio Scriptures have opened new doors for hearing God’s Word, many now recognize that literacy could help them go deeper. Yet the reality on the ground is sobering.

‘We want to learn to read our language’, says Timothy Wakson, translator and literacy teacher with the Rishiwa Project from Kaduna State. ‘But we don’t have teachers.’

‘There are people here who are willing to learn, but we lack the materials and funds’, added Pastor Riga Andrew, who helps coordinate literacy efforts alongside OBT work with the Miship Project in Plateau State. ‘Trained literacy teachers are also scarce. In some cases, facilitators rely on volunteers with no formal training to carry out basic instruction. We’re trying, but if there’s no investment in training our people, it’s hard to keep the momentum.’

•••

‘Without greater financial support and properly equipped teachers, the full potential of OBT may remain out of reach.’

Geoffery, from Mbang Project

Shifting perspectives

Despite these challenges, the impact of combining orality with literacy is starting to show.

‘Now, when we listen to the audio Bible, we can follow along with what little we’ve learned’, Geoffery said. ‘It stays in our hearts longer. We are seeing the beauty of having God speak in our language.’

For many communities, the true strength of OBT and literacy efforts lies not just in the tools or techniques, but in the faithful presence of local facilitators who are there every day. They help translate, they teach literacy and they lead Scripture listening groups.

‘These are not outsiders who fly in and leave’, says Miss Gift Yakubu, a youth in the Loh community. “The people teaching us are from here. We see them in the market. We worship together. That makes us trust the process more.”

While some community members were initially unsure about learning to read their mother tongue—a language long viewed as inferior to English or Hausa—the steady work of OBT teams has shifted perspectives.

‘Their presence reinforces the message: Your language matters, your faith matters, and both belong together.’

Rev. Dr. Ibrahim Amshi, NBTT’s OBT Director-Coordinator

Story and photos: Aondongusha Joshua Tsar in Nigeria