‘We have achieved what we thought was impossible: uniting the organisations.’

Leonardo Sirit

Facilitator of the Venezuela mesa for Bible translation, and Director of DGM Venezuela

•••

Venezuela

Introducing the mesas concept in Venezuela was not easy at first. Organisations interpreted the invitation from the mesa facilitators as an attempt to exert control, Leonardo Sirit, Director of DGM and mesa facilitator, said.

“But then we made them understand that we are not their bosses,” he said. “What we wanted was not leadership here, but a helping hand to bring us all together. Where we can all talk, where we can all listen, where we can all share.”

Soon, mesa participants began to invite others. By 2024, six years after the Venezuela mesa’s beginning, leaders from 13 organisations gathered to continue dialogue and building relationships as partners in the country’s Bible translation movement.

Brazil

In Brazil, Raquel Villela helped to lay the foundation for collaboration in 2019 when she organised a national Bible translation conference in Curitiba, attended by a number of Bible translation organisations. Raquel would become the first coordinator for the Aliança pela Tradução da Bíblia, the Bible translation table in Brazil.

Now Raquel is transferring the coordinator role to Paolo Teixeira, Director of Institutional Relations, Bible Society of Brazil. Paolo said he can see God’s hand at work in his service, allowing him to build relationships over the years with churches and Bible translation organisations.

“The table is a refinement of what was born organically,“ he said.

It helps that Brazil has a collaborative culture.

“We like to cooperate, to dialogue,” Paolo said. “So we plan, but we are flexible. That’s more or less the DNA of Brazil.”

He has found things similar in Latin America.

“When I worked with [people in] Europe,” he said, “planning was the basis. In Latin America, relationships are the basis, and trust.”

For Paolo, that network came in handy when planning a Bible translation conference in March. The Primeiro Simpósio de Tradução Bíblica no Brasil (the first Bible translation symposium of Brazil), was held in São Paulo, Maranhão state. A total of 150 people from 25 translation organisations attended and/or presented.

Paulo invited people from four organisations to help plan the content and speaker invitations. One of those people was Raquel, who offered suggestions on how the program should be paced for Brazilian culture.

“For example,’ Paulo said, ‘we didn’t have 12 talks a day. We had eight, and four spaces were for dialogue, for walking, for eating together. And that’s where the concept of the table comes in. So it was organic. It wasn’t an event organised by the table, but it had the spirit of the table and of cooperation. Many organisations came and everyone participated – the small ones, the big ones, the newest ones, the oldest ones.”

God answered their pre-conference prayers for strengthening ties across organisations.

“We all left convinced that we can grow more as a translation movement if we unite more,” Paolo said. “Because one person lacks a consultant, another lacks [something else] … and that’s where we exchange the resources that God has given us.“

“People left with the feeling that we had achieved something important. And the role of the Bible translation table emerged at the end. It was born out of the cooperation that already existed.”

Colombia

Through contacts they made with the Colombia mesa, SIL Global staff met with the Colombian Bible Society, Global Partnerships and the Piapoco Church to ask how they could best serve the Piapoco Old Testament project. Each organisation plays a different role within that project. More recently, the Colombian Bible Society invited SIL to provide consultant help for literacy projects in two communities with recently completed Bibles, the Wayu and Nasa.

“And this happens through the confidence that has been built through the values of the mesa,” said David Pickens, Translation Projects Facilitator and a consultant-in-training with SIL Global. “So, there’s trust built there. There’s a platform for collaboration.”

In 2024, SIL was invited to collaborate in a literacy project for the Ese Ejja community in Bolivia, along with Ethnos 360 and the Bolivian Bible Society. Ethnos 360 had participated in the Ese Ejja New Testament translation in a related dialect, and provided access and editing rights to all the materials they had produced, including primers, in order to adapt the materials for the needs of the new literacy project. The Bolivian Bible Society printed 1,000 copies of that first Ese Ejje primer without charge, specifying that they did not need their name to appear in the books, but were simply glad to participate.

“So, it was a genuine desire to collaborate and not promote themselves,” David said. “That kind of collaboration didn’t happen out of the blue. It happened because we were able to relate to these people in a safe environment where we have a common vision for moving forward and can develop significant trust. So, I’m a fan. I’m a cheerleader.”

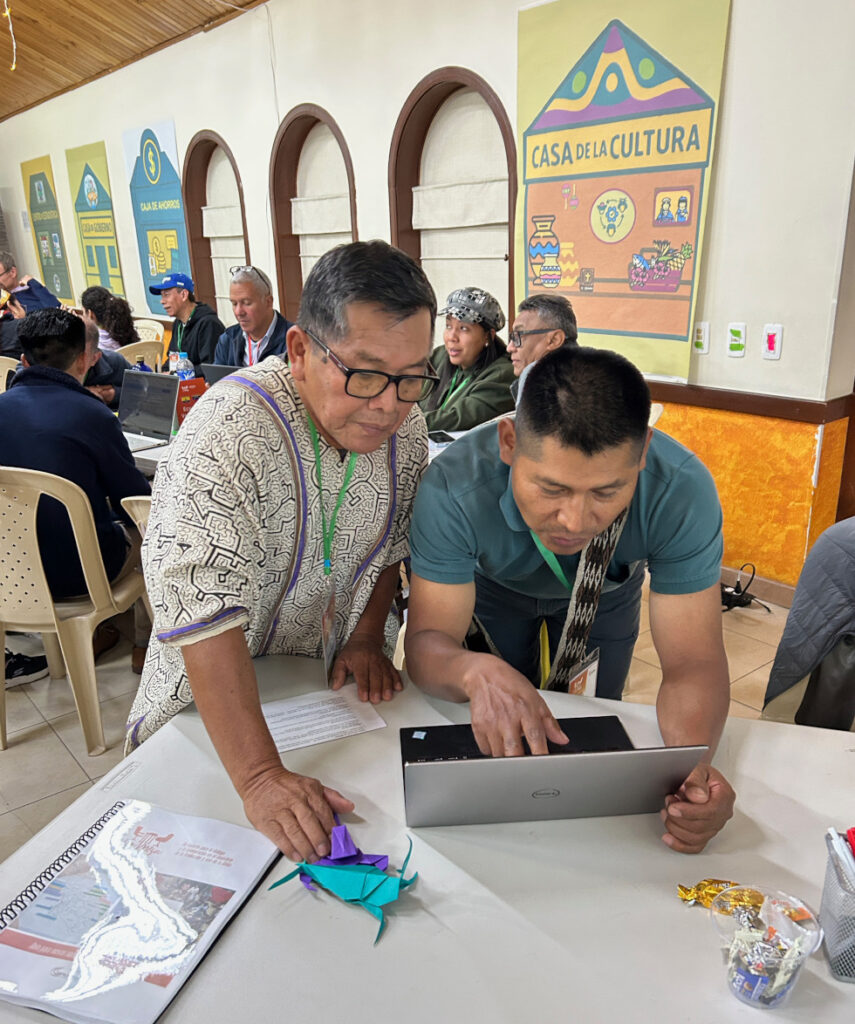

Peru

Rafael Arimuya is director of the Red Trans Amazonica (Trans Amazonica Network), a facilitator for the Peru mesa, and a member of the mesas peripheral team.

“Before, there was a lot of prejudice among indigenous people against mixed-race nationals and foreigners,” Rafael said, “and nationals against indigenous people. But when we understand each other, we respect each other and find the potential in each other. For example: Indigenous people have their own resources to contribute to a project. Foreigners also have their resources. The national church also has theirs. Indigenous people may not have economic resources, but they have natural resources that can be shared, and they know how to survive in the jungle, which they can teach to foreigners and nationals alike. So that’s something tremendous. Likewise, we indigenous people can learn from foreigners their punctuality and integrity, things we are not accustomed to. In this way, we help each other.”

Members of the Peru Mesa have also been able to depend on mutual generosity. For their first mesa retreat, they had enough funds to cover the costs of travel, food, etc. But for the next gathering, they didn’t. Representatives of each organisation, whether foreigners, nationals or indigenous, paid for their own expenses.

“At the last minute, we even had to pay for an auditorium to hold the conference,” Rafael said. We didn’t have the money, so we collaborated among ourselves. We collaborated right there and then, and we still had money left over. And so we thought: Well, we’ll continue doing it this way, whether there is funding from outside sources or not. We are entering a stage of [greater] collaboration.”