A Peru-Malaysia connection energises teams for new approaches in oral communities

As Bible translation movements become increasingly connected globally, translators are finding that innovative methods can cross cultures, too.

One example is oral Bible translation (OBT), a strategy spreading in many parts of the world where communities tend to engage best with translation as an oral process rather than written.

Evelyn Gan of Wycliffe Malaysia had taught OBT workshops in Asia, but she never expected to do this half a world away. She serves as the Wycliffe Global Alliance’s Consultant for Oral Translation Programmes. In May, she and her small team found themselves in front of a room full of translators and related staff in Peru, teaching OBT principles.

‘OBT wasn’t what I thought’

OBT does not mean just reading aloud from a written translation. Audio recordings have their usefulness, but oral language can be quite distinct from written. The biggest discovery for participants was, Evelyn said, ‘the importance of considering the audience’s language use, understanding and context, even within the same language.’

Some of the Peru attendees were a bit skeptical at first. Pastor Luis Cervantes, Director of AIDIA (Asociación Interdenominacional para el Desarrollo Integral de Apurímac)and Executive Secretary of ACIEP (Asociación Cristiana Interétnica del Perú), expected the same approach he encountered at a past oral translation course, in which a facilitator would ask a native speaker to translate one sentence or verse at a time, in isolation.

This year’s training allayed his concerns.

‘OBT wasn’t what I thought’, he said.

Now he’s excited about using OBT strategies in translation and Scripture engagement efforts in Peruvian communities where communication is mostly oral, and where traditional literacy-based methods have not taken hold.

‘Doing it orally is really good,’ he said, ‘because everybody has to participate. At the end of this year and the start of next year, we are going to initiate four more translation projects. We can start the process with the internalisation part.’

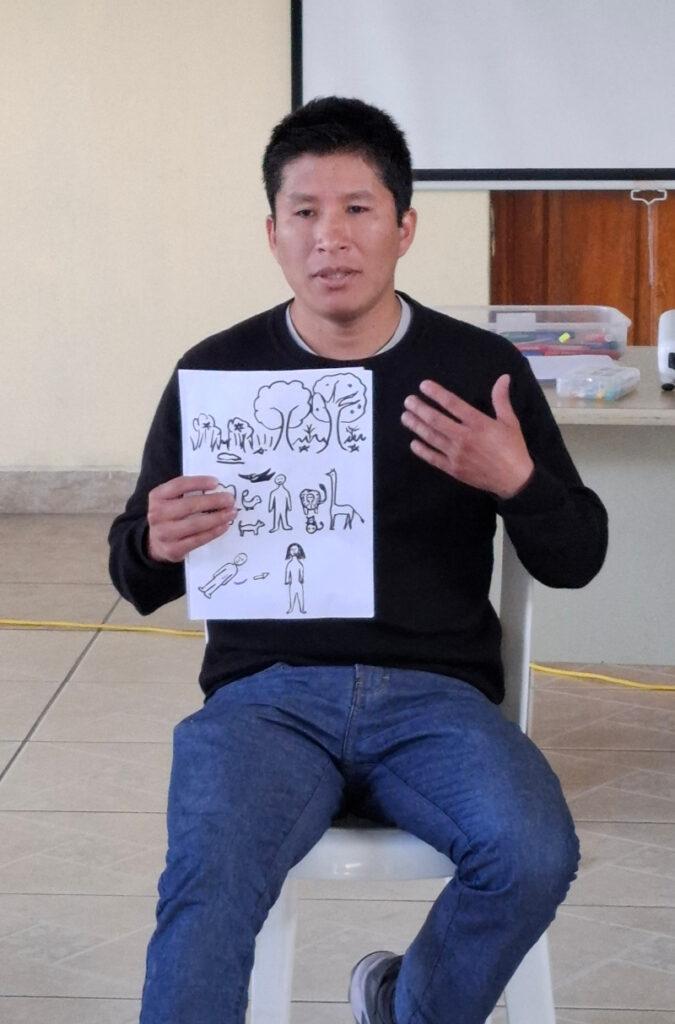

‘Internalisation’ is the key idea in OBT. Translation facilitators listen to various translations of a passage and learn about the cultural and historical background. Through discussions, acting it out, using drawings and storyboards, they absorb the meaning and details of the passage so deeply that they are able to share orally what they’ve learned with a team of oral translators, often using equally creative and engaging methods.

From Asia to the Americas

Evelyn not only helped facilitate OBT trainings in Malaysia, she also has served as a consultant for an oral translation into her primary language, Penang Hokkien. In 2024, she helped with a training session in Penang, Malaysia that blended OBT training methods from diverse approaches, and included trainers and participants from a variety of organisations.

Then, a series of conversations among some Alliance organisation leaders, plus Alliance area leadership in Asia and the Americas, led to a connection for presenting the same workshop in Peru. Evelyn gathered a team from Wycliffe Malaysia to lead the workshop, even though none of the training team spoke Spanish. In May 2025, Evelyn, along with Poh Swan Ng, Tomomi and Irene Chen, presented a two-week OBT training to 13 translators, translation facilitators, administrative staff and Scripture engagement workers who serve in Bible translation. The training took place in Abancay, a city of 58,000 people in southern Peru. Wycliffe Malaysia not only provided the trainers, but also helped provide their travel funding, drawing partly on some start-up funding from Seed Company.

‘This trip showed me how powerful cross-organisational partnerships can be’, she said. ‘With AIDIA, Wycliffe Global Alliance and Wycliffe Malaysia, everyone played a part. It was a beautiful picture of what a community serving one another looked like.’

One challenge for the Malaysians was teaching across language barriers. They taught in English (not their first language) to Spanish speakers, through interpreters.

‘Overall, this workshop helped me better understand the importance of adapting content to the participants’ pace and needs’, Tomomi said, adding that she learned a lot about overcoming language barriers in teaching interculturally. ‘Above all, it was a reminder of the resilience and humility of those we serve.’

‘God is always orchestrating things behind the scenes, bringing people together and making the connections’, Lay Leng said. ‘I had so many questions in my mind initially—excited, and at the same time doubtful that this would materialise. Well, yes, it did materialise. This is really God’s mission and we are so thankful to be part of it.’

Intercultural learning

Yuly Vedia, an assistant administrator, had expected a mostly theoretical, lecture-style workshop. Instead, Evelyn’s team led the group through hands-on exercises like dramatisation, drawing, storyboarding and oral retelling. In short, they taught OBT using oral learning styles.

In the process, workshop participants gained practical experience with the stages of OBT—which are not all that different from written translation: source language comprehension, internalisation, oral drafting, testing, revision and checking.

‘Putting it into practice was really amazing’, Yuly said. ‘Doing it together helps to learn the process.’

In turn, trainers gained fresh perspectives. Through participants’ creativity and insight, Evelyn said, they ‘inspired us as facilitators to reflect on new ways of conducting oral devotions’.

‘A structured, community-driven approach to translation’

Although AIDIA staff were already using oral storying methods prior to the training, most did not have a clear understanding of OBT as a structured, community-driven approach to Scripture translation, Evelyn said. In fact, Director Luis Cervantes was initially unconvinced of the practicality of OBT. For example, he questioned how a Quechua pastor who was teaching from a passage in Matthew and would reference something in the Psalms.

‘How is he going to do that with an oral translation?’ he said. ‘Does he have to look for it on his cell phone? How does that work? So, I had many doubts.’

‘The OBT that they taught us was more like hearing the biblical passage or story over and over again’, he said, ‘and people have to hear and internalize the entire story in their mind. And they have to narrate the story naturally.’

‘I think that in general terms the entire training was a great blessing because it made us reflect on another way of learning, another way of teaching, another way of how we could use the Bible in the communities as well.’

Applying oral strategies to translation in the real world

Participants left with enthusiasm about what they learned and appreciation for how OBT strategies can apply in their contexts.

‘I had no idea what oral Bible translation was,’ Bernardino Lancho, a mother-tongue Quechua translator said. ‘I thought it was just one person standing up and telling Bible stories.’

He said the oral strategies they learned would apply well even in their written translation project. (His team is currently translating the Old Testament.)

‘I think it is a good fit for our community because it is more oral than literate’, Bernardino said. ‘I will put that into practice: using the Bible that we have and translating it orally.’

AIDIA is looking at OBT methods, in particular internalisation, as a useful strategy for Scripture promotion. ‘We found it to be very participative and communicative’, Luis said.

They also are talking about including OBT as an initial strategy in new translation projects, ‘to help the facilitators or the local translators to internalise more the passage that they are going to translate,’ Luis said. ‘So there would be two steps: the first step, an oral translation, and the second step would be to put that oral translation into written form.’

Learning by doing

To practice OBT, workshop participants were divided into three groups with different target audiences. One chose to translate for a Quechua community in Abancay where the workshop was held, one chose the community of young people who speak Spanish in Abancay, and the third chose a Spanish-speaking migrant community with syncretistic beliefs. The two groups translating for Spanish speakers based their translation exercises on Spanish Bible passages that had been adjusted to fit the dialect of their target audiences.

‘I felt a little uncomfortable at first,’ said Yoliño Vasquez, a translation facilitator who participated in one of the Spanish dialect groups. ‘But I realised that it is doing translation to meet the needs of our audience— thinking about what the passages mean, and translating them faithfully to reach out to a certain group.’

Which leads back to the idea of internalising Scripture.

‘For us it was very interesting because it made us think that this way of internalising would help many people to understand the biblical story more accurately’, Luis said. ‘Because it is a whole process of hearing it over and over again and being able to narrate that story.’

‘I have some experience with orality’, said Dina Rojas, who serves in Scripture engagement, ‘but this workshop helped me to know how to dig deeper into the passage by using questions.’

This deeper level of understanding has applications even for written translation, Evelyn said. Not taking time to grasp the full meaning of a passage can result in an overly literal or surface translation. Internalisation allows translators to take time to fully understand what a passage is saying, so they can strive for accuracy, and not just ‘getting the words right’.

The power of oral translation

One distinction between written translation and oral translation is that teams need to consider what Evelyn calls ‘emotional exegesis’. What tone of voice do you use? Where do you put appropriate pauses? How do you record direct speech? For example, in a previous interview, Evelyn referred to Mark 8:33, when Jesus rebukes Peter. Did he do it sternly? Did he raise his voice? When telling the story, do you have to raise your voice? (see Through a Consultant’s Eyes: A Glimpse of Oral Bible Translation). Understanding and relating to a Scripture passage on an emotional level helps to make a translation more memorable and engaging.

‘At the beginning, we didn’t know what to expect’, said Cirilo Vasquez, a translator. ‘Personally, I think the emotion part is really impactful. For people who don’t read, this is important.’

For several years, AIDIA has used oral Bible storying accompanied by a book of illustrations as a Scripture engagement strategy. It was popular not only with people who could not read, or with children, but with everyone, Luis said.

‘And now that we have received training in oral translation of the Bible’, he said, ‘I would say that almost 40 percent of the training is similar to what we were doing, with the difference that here they taught more about internalising the stories.’

Luis expects that pastors in oral communities will receive this approach well.

‘Hearing the stories, telling the stories, repeating the stories – I think that’s going to help them a lot’, he said. ‘I think they are going to be delighted’.

Story: Gwen Davies and Jim Killam, Wycliffe Global Alliance

Alliance organisations may download and use the images from this article.

See also:

Through a consultant’s eyes: A glimpse of oral Bible translation